- 请教张维为,知道无耻怎么写吗? [2019/01]

- 论言论自由 [2020/01]

- 中国为什么应该坚决抛弃佛教(1) [2020/06]

- 在文革中被迫害致死的美女们 [2018/11]

- 龙应台:听了于丹的演讲我真想自杀! [2019/07]

- 刘少奇诞生120周年群丑图 [2018/11]

- 从《五·七一工程纪要》到习家军 [2018/10]

- 毛泽东侄女文革遭火烤下体惨死内幕 [2018/11]

- 世界大瘟疫,中宣部很兴奋 [2020/03]

- 大学:群兽乱交和群魔乱舞 [2018/04]

- 恶梦。(记北京四中文革前的四清) [2018/09]

- 罪恶的习近平主义 [2018/09]

- 周有光:中国人读的许多历史都是假历史 [2019/01]

- 习近平2018年12月的大撒币之旅 [2018/12]

- 赤裸裸的谎言:“台湾,凭什么让我原谅你” [2018/12]

- 回国留学生萧光琰一家之死 [2018/10]

- 评“华二代坦言生存真相: 既不被美国圈子欢迎,也不被中国人接纳” [2018/12]

- 恶梦。续一。(记北京四中文革前的四清) [2018/09]

- 从中兴变局看中国产业弊端 [2018/04]

- 武汉瘟疫与中国模式的破产 [2020/02]

- 文革余毒习近平 (上) [2018/10]

- 今天你汉奸了吗? [2018/06]

- 扫购口罩的华人有错吗? [2020/04]

- 北大教授郑也夫:统治者的任性是我们惯坏的 [2019/01]

- 小议知识产权 [2018/07]

- 终结美国种族主义的最后一战? [2020/09]

Photo: Sarah Anne Ward

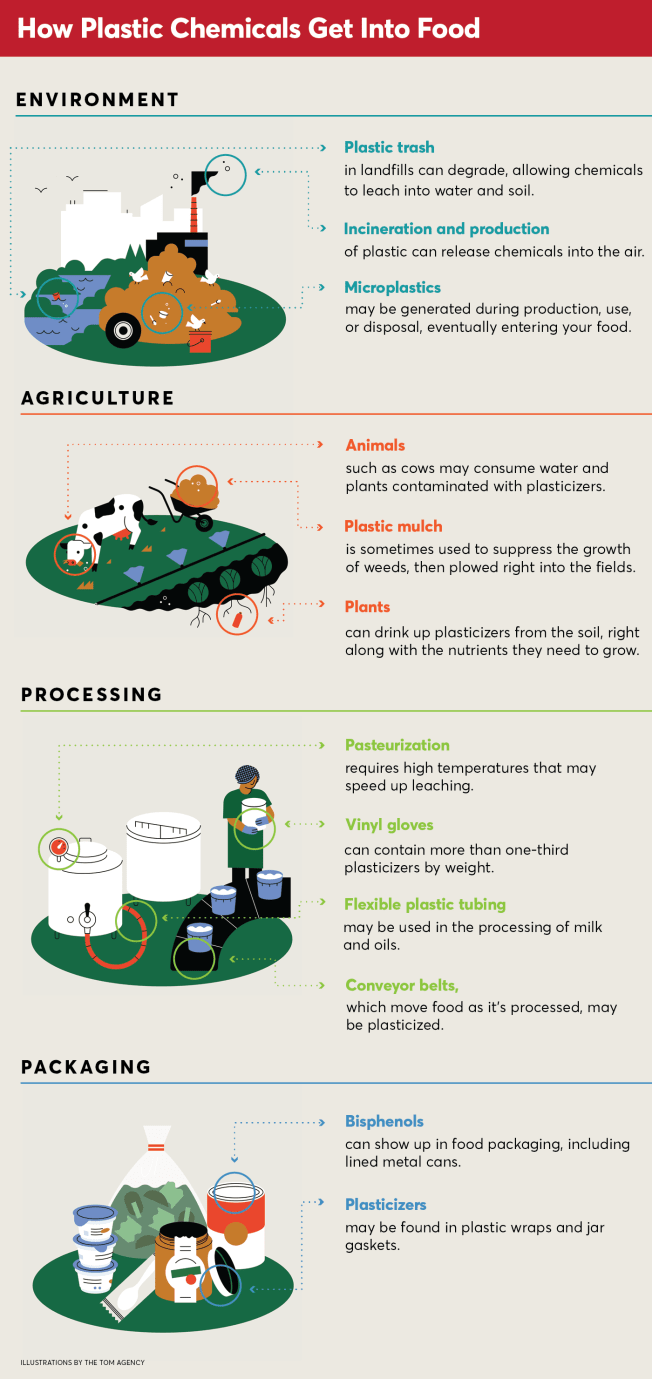

Photo: Sarah Anne WardBy the time you open a container of yogurt, the food has taken a long journey to reach your spoon. You may have some idea of that journey: From cow to processing to packaging to store shelves. But at each step, there is a chance for a little something extra to sneak in, a stowaway of sorts that shouldn’t be there.

That unexpected ingredient is something called a plasticizer: a chemical used to make plastic more flexible and durable. Today, plasticizers—the most common of which are called phthalates—show up inside almost all of us, right along with other chemicals found in plastic, including bisphenols such as BPA. These have been linked to a long list of health concerns, even at very low levels.

Consumer Reports has investigated bisphenols and phthalates in food and food packaging a few times over the past 25 years. In our new tests, we checked a wider variety of foods to see how much of the chemicals Americans actually consume. The answer? Quite a lot. Our tests of nearly 100 foods found that despite growing evidence of potential health threats, bisphenols and phthalates remain widespread in our food.

Bisphenols and phthalates in our food are concerning for several reasons.

To start, growing research shows that they are endocrine disruptors, which means that they can interfere with the production and regulation of estrogen and other hormones. Even minor disruptions in hormone levels can contribute to an increased risk of several health problems, including diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, birth defects, premature birth, neurodevelopmental disorders, and infertility.

Those problems typically develop slowly, sometimes over decades, says Philip Landrigan, MD, a pediatrician and the director of the Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good at Boston College. "Unlike a plane crash, where everyone dies at once, the people who die from these die over many years."

Another concern is that with plastic so ubiquitous in food and elsewhere, the chemicals can’t be completely avoided. And though the human body is pretty good at eliminating bisphenols and phthalates from our systems, our constant exposure to them means that they enter our blood and tissue almost as quickly as they’re eliminated. And plasticizers in particular can easily leach out of plastic and other materials. In addition, the chemicals’ harmful effects may be cumulative, so steady exposure to even very small amounts over time could increase health risks.

All that makes it difficult to trace any particular bad health outcome—say, a heart attack or breast cancer—to the chemicals. And it makes it hard for regulators to set a limit for what is considered safe for any food. "As a first step, the key is to determine how widespread the chemicals are in our food supply," Rogers says. "Then we can develop strategies, as a society and individually, to limit our exposure."

To help figure out the scope of the problem, CR tested a wide range of food items, in a variety of packaging.

Specifically, we tested 85 foods, analyzing two or three samples of each. We looked for common bisphenols and phthalates, as well as some chemicals that are used to replace them. (Read more about these chemical substitutes.) We included prepared meals, fruits and vegetables, milk and other dairy products, baby food, fast food, meat, and seafood, all packaged in cans, pouches, foil, or other material.

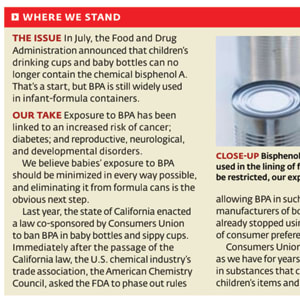

The news on BPA and other bisphenols was somewhat reassuring: While we detected them in 79 percent of the tested samples, levels were notably lower than when we last tested for BPA, in 2009, "suggesting that we are at least moving in the right direction on bisphenols," says CR’s Rogers.

But there wasn’t any good news on phthalates: We found them in all but one food (Polar raspberry lime seltzer). And the levels were much higher than for bisphenols.

Determining an acceptable level for these chemicals in food is tricky. Regulators in the U.S. and Europe have set thresholds for only bisphenol A (BPA) and a few phthalates, and none of the foods CR tested had amounts exceeding those limits.

But "many of these thresholds do not reflect the most current scientific knowledge, and may not protect against all the potential health effects," says Tunde Akinleye, the CR scientist who oversaw CR’s tests. "We don’t feel comfortable saying these levels are okay," he says. "They’re not."

The decision to allow these chemicals in food "is not evidence-based," says Ami Zota, ScD, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who has studied the risks of phthalates.

For example, one of the most well-studied phthalates is called DEHP. Studies have linked it to insulin resistance, high blood pressure, reproductive issues, early menopause, and other concerns at levels well below the limits set by American and European regulators. It was the most common phthalate that we found in our tests, with more than half of the products we tested having levels above what research has linked to health problems.

In addition, Akinleye says that with exposure to these chemicals coming from so many sources—not only food but also other products, such as printed receipts and household dust— it’s difficult to quantify what a "safe" limit would be for a single food. "The more we learn about these chemicals, including how widespread they are, the more it seems clear that they can harm us even at very low levels," he says.

The 67 grocery store foods and 18 fast foods CR tested are listed in order of total phthalates per serving. While there is no level that scientists have confirmed as safe, lower levels are better. Our results show that although the chemicals are widespread in our food, levels can vary dramatically even among similar products, so in some cases you may be able to use our chart to choose products with lower levels.

Growing concerns about the health risks posed by these chemicals have led U.S. regulators to meaningfully curtail the use of these chemicals in a number of products—but not yet food.

For example, the federal government has banned eight phthalates in children’s toys. But, with the exception of a 2012 ban on BPA in baby bottles (extended in 2013 to infant formula cans), there are no substantive limits on plastic-related chemicals in food packaging or production. Although the Food and Drug Administration no longer allows certain phthalates in materials that come into contact with food, the agency updated its regulations only after those chemicals were no longer in use. And just last year, it rejected an appeal from several groups calling for a ban on multiple phthalates used in materials that come into contact with food.

An FDA spokesperson told CR that in 2022 it asked the food industry and others to provide the agency with additional data about the use of plasticizers in any material that comes into contact with food during production, and might use that information to update its safety assessments of the chemicals.

CR’s food safety scientists and others say such a reassessment by the FDA and other agencies is overdue and essential. “Since bisphenols and phthalates are hazardous chemicals, they should not be allowed at all in food-contact materials,” says Erika Schreder, the science director at Toxic-Free Future, an advocacy group.

Supermarket and fast-food chains, as well as food manufacturers, should also be required to take action, Rogers says, and should set specific goals for reducing and eliminating bisphenols and phthalates from all food packaging and processing equipment throughout their supply chains.

CR contacted certain companies in our tests that had products with the highest phthalate levels per serving, and asked them to comment on our results. Annie’s, Burger King, Fairlife, Little Caesars, Moe’s Southwest Grill, Wendy’s, and Yoplait did not respond to our requests for comment.

Del Monte, Gerber, and McDonald’s emphasized that they abide by existing regulations. Gerber added that it requires its suppliers to certify that its food packaging is free of BPA and phthalates. Chicken of the Sea said it requires its suppliers to certify that neither products nor packaging has intentionally added BPA or phthalates, but it acknowledged that fish live in water that is often polluted with phthalates.

More chemical companies need to step up, too, by creating safer, more sustainable materials. "We want things to be functional, but also nontoxic and biodegradable and renewable," says Hanno Erythropel, PhD, at the Center for Green Chemistry and Green Engineering at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

That may be tough, he acknowledges, but it should be possible: An entire field called green chemistry is working to develop just these sorts of alternatives.

In the meantime, see our advice on what you can do now to limit your exposure to these chemicals.

Out of Our Food, 1998-2024

1998

CR finds plasticizer chemicals called phthalates in some plastic wraps and cheeses, and asks the FDA to eliminate the chemicals from the food supply.

1999

CR finds that BPA in plastic baby bottles can leach into infant formula and advises parents to throw away bottles that could contain the chemical.

2009

CR finds BPA in nearly all 19 tested foods and calls on government agencies to eliminate the chemical in materials that come in contact with food.

2012

CR praises the FDA for banning BPA in baby bottles and sippy cups but calls on the agency to also ban the chemicals in infant formula containers and food cans. The FDA does so the following year.

2023

CR does not find BPA, lead, or certain phthalates in nine baby bottles but warns that related chemicals could still be present and cautions parents to consider using glass or silicone bottles.

2024

CR finds phthalates and related chemicals in nearly all 85 foods tested and calls on the FDA to get the chemicals out of food.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article published in the February 2024 issue of Consumer Reports Magazine incorrectly identified one of the products. It should have been Brisk Iced Tea lemon, not Lipton Brisk Lemonade. In addition, the package descriptions for several products in the chart of tested products have been changed to more accurately describe the materials used.