Young, educated, and successful, Mabel Lee had a bright future ahead of her in 1924. She was the daughter of a prominent Chinese American pastor and community leader, she had recently finished a PhD, and her work to promote women’s suffrage had been covered by The New York Times. She was well-connected with the emerging leaders in China and was just beginning to establish her own place in shaping its future when tragedy struck. Her father, who had dedicated his life to ministering to the Chinese American community in New York, passed away suddenly, leaving his ministry and his family behind. Astonishingly, Mabel chose to give up her incredible opportunities in China to return and carry on the ministry her father started, a ministry that still endures today.

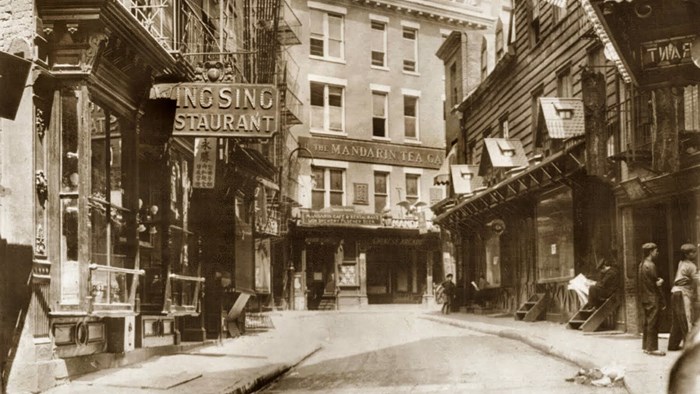

The early 20th century was an extraordinarily difficult period for Chinese Americans. Decades of federal legislation prohibiting Chinese working class immigrants from coming to America had taken its toll. Exclusion laws resulted in an overwhelmingly male Chinese population. Residential racial segregation created the urban ghettos that became America’s Chinatowns. In turn, these communities were riddled with tensions between rival fraternities, family associations, and political factions (known as tongs) that often engaged in human trafficking and violent crimes. Popular opinion considered Chinese people “heathen” and perpetual foreigners.

Protestant missionaries and Chinese converts were among the few that engaged Chinese immigrants, often driven by evangelistic and social reform motives. Many missionaries and converts also publicly refuted popular opinions of the Chinese, portraying them (especially the American-born) in reports, magazines, and even Congressional hearings as fully capable of becoming Americans. Despite their efforts, Christians made up a tiny percentage of the Chinese American population and missions’ efforts were solely dependent on the support of Protestant denominations.

Enter Mabel Lee and First Chinese Baptist Church, New York City. Under Mabel’s leadership as de facto pastor of the Chinatown-based church and social service organization, First Chinese Baptist Church became the first self-supporting Chinese church in America. A graduate of Colombia University with a PhD in economic history, the Chinese American community leader led the church for more than 40 years. It still exists today.

Christian, Suffragist, ScholarMabel was the only daughter of a pioneering pastor and missionary, the reverend Lee To (1868–1924). Born in Guangzhou, To came to the United States in 1880 as a contract laborer just two years before the Chinese Exclusion Act (CEA) banned labor immigration. To learned English at a missionary school, an asset that helped him gain standing as a merchant and consequently adjust his immigration status. (The CEA didn’t apply to merchants and clergy, who were allowed to travel between China and the US freely.)

Learning English wasn’t the only significant life change To experienced after he arrived in America. In 1890, To became a Christian at a Chinese mission in San Francisco. Three years later, he gave up his business and enrolled in a Baptist seminary in Guangzhou. After To completed his theological training in New York City, the American Baptist Home Mission Society appointed him first to be a missionary to the Chinese in Washington State in 1898 and then as a minister at the Morningstar Mission in New York City’s Chinatown in 1904. To thrived in his work in Chinatown and gradually became a member of the community’s elite. In 1921, he became the president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society, the leading Chinese American coalition of powerful Chinese family associations. Because he discouraged traditional Chinese religious practices and modernized and Americanized Chinatown, American Baptists hailed him as the “Christian mayor” of Chinatown.

To’s daughter, Mabel, was born in Guangzhou in 1896. She spent her early childhood in China and enrolled in a missionary school where she became proficient in English. She reunited with her parents shortly after her father was appointed to the Morningstar Mission and attended New York City’s public schools until she was accepted to Barnard College. Mabel then earned a PhD in economic history at Columbia University in 1921.

Mabel proved to be a gifted communicator and an ambitious young leader who was dedicated to improving society, especially for women and for China. Like suffragist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, she argued that modern democracy could not survive without woman’s suffrage. In the May 1914 issue of The Chinese Student Monthly, Mabel argued that woman’s suffrage or the early feminist movement was “nothing more than the extension of democracy or social justice and equality of opportunities to women.” Mabel’s prominence grew; in 1915, her speech at a suffrage workshop was covered by The New York Times.

Mabel was also passionate about her home country, arguing that its future success relied on its commitment to women’s equality. “The welfare of China and possibly its very existence as an independent nation depend on rendering tardy justice to its womankind,” she wrote. “For no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization unless its women are following close to its men if not actually abreast with them.”

After completing her studies, Mabel anticipated returning to China and taking her place among a new generation of national leaders and social reformers. She was not the only one who envisioned this future. Two years after Mabel earned her PhD, a local Baptist newspaper reported that

From France, Mabel wrote, “I do thank God for the United States which gave me such wonderful opportunities for development and such a keen insight into the realms of knowledge. I feel that my life must be devoted to helping my own people in China.”

Mabel was invited to become dean of women at a Chinese institution, University in Amoy, and appeared to have numerous professional opportunities in America as well. But the following year, as she explored opportunities in China, a tragic turn of events forced her to reconsider her plans.

Church Builder and Community ServantAmong Mabel’s father’s many accomplishments was his ability to reconcile rival factions. But the stress of this work took on a toll on his health. In late November 1924, while brokering peace between two dueling tongs over dinner, To had a fatal heart attack or stroke. Mabel immediately returned from China to New York City to care for her mother and assume responsibility for her father’s mission.

At the time of his death, the Chinese mission had been renting its facilities. But Mabel wanted the organization to have its own building. She initiated a successful campaign to acquire a building in Chinatown in memory of her father after pooling together funds raised from the Chinatown community, a personal loan, and a loan from the denomination’s mission’s body. The mission, now the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City, still stands in the heart of Chinatown today.

After purchasing the building, Mabel was still reluctant to stay. She had never pursued ministry. During a visit to China in 1929, she wrote wistfully, “It seems that China is run by my personal friends. One is head of this University and another of that; one is in charge of all the railroads in China, and another of Finance or Education.”At the time of his death, the Chinese mission had been renting its facilities. But Mabel wanted the organization to have its own building. She initiated a successful campaign to acquire a building in Chinatown in memory of her father after pooling together funds raised from the Chinatown community, a personal loan, and a loan from the denomination’s mission’s body. The mission, now the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City, still stands in the heart of Chinatown today.

But hope for a temporary stay in New York faded as political conditions in China worsened. It also became evident that the survival of the mission during the Great Depression depended on Mabel’s skills. Most importantly, she could not suppress what she shared in common with her father: a passion for winning souls for Christ and a determination to engage the social problems of Chinatown.

In the 1930s, New York City’s Chinatown demographics were on the brink of change. At the beginning of the decade, the neighborhood had a 10:1 ratio of men to women. The population of children and families grew slowly, even after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. After World War II, however, war brides and refugees increased the Chinese American population dramatically and created an urgent need for spiritual and material care. Mabel’s educational background and bilingual skills were invaluable for bridging the gap between Chinese people and the wider English-speaking community during this time.

Mabel never married, though she was courted while in college. Instead, she dedicated her entire life to the Chinatown community. Mabel preached and taught each Sunday. She mobilized Christians from white churches to share the gospel with and serve the people of Chinatown. She organized classes in English, typewriting, radio, carpentry, and other skills for working class Chinatown residents and later, for newly arrived immigrants and their children.

Most significantly, Mabel helped make the Chinese mission a self-supporting and independent congregation by growing its membership and raising support from the wider community. This was a timely achievement. Mainline Protestant mission boards stopped supporting ethnic-specific churches and missions by the mid-20th century, fueled by beliefs that the assimilation of immigrants and the integration of African Americans were the inevitable final steps toward a non-racial society. The proliferation of hundreds of independent-minded Chinese churches in America since Mabel’s death in 1966 and the persistence of ethnically and racially distinct churches and community organizations today have proven these beliefs as—at best—premature.

The Salvation of ChinaThe doors of First Chinese Baptist Church, New York City are still open today. Its current pastor even has the surname Lee. The church has continued to focus on welcoming immigrants and unifying the neighborhood, seemingly echoing a vision Mabel laid out so many years ago. By the end of World War II, mainstream American perceptions of Chinese Americans had changed drastically from early 20th century perceptions. As allies in the struggle against Japan, the Chinese garnered greater respect from Americans. Chinatown’s rival factions declared a truce in order to unify around China’s war efforts. Many Chinese church leaders joined or led efforts to rehabilitate the image of Chinatowns across the country, often by promoting them as cross-cultural educational opportunities (or, alternately, exotic dining and tourist traps).

“Let us therefore not forget the significance of our work in the mission. It may seem very small, but the influence is very vast,” wrote Lee just before her work truly started in 1925. “Every little we put in counts. [Let us] rededicate ourselves to our tasks, that every boy who comes into the Mission will be made to know Christ. Christianity is the salvation of China, and the salvation of the whole world.”

Tim Tseng, PhD, is the pastor of English ministries at Canaan Taiwanese Christian Church in San Jose, California, and affiliate of Fuller Theological Seminary’s Asian American Center. He is the founder and former executive director of the Institute for the Study of Asian American Christianity. His blog is timtseng.net

3270

3270